Revised text

of a presentation to the residents and Interns in Internal Medicine at Long

Island Jewish Hospital. Given in 1982 at the request of Dr. Herbert Diamond, the Chief

of Medicine, after I described to him the effect of Aesthetic Realism on me in

my hiring interview.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I have seen that the philosophy Aesthetic Realism can help medical students, residents, attending physicians like myself,

and all other medical personnel, be kinder, more insightful, and more ethical.

This philosophy was founded by the American poet and critic Eli Siegel, and its

major text is Self and World: An Explanation of Aesthetic Realism.

Aesthetic Realism is taught in classes,

seminars, programs and individual consultations at the Aesthetic Realism Foundation in New York City. The main principles of Aesthetic Realism, stated

by Eli Siegel, are:

One, Man's greatest, deepest desire is to

like the world honestly.

Two, The one way to like the world

honestly, not as a conquest of one's own, is to see the world as the aesthetic

oneness of opposites.

Three, The greatest danger or temptation

of man is to get a false importance or glory from the lessening of things not

oneself; which lessening is Contempt.

Liking the World

Aesthetic Realism explains that our

deepest desire is to like the world. We want to see the world as on our side,

as deeply friendly and for us. This is true of every doctor and every patient.

Every patient hopes that the doctor, the nurse, the receptionist, as

representatives of the world and of medicine, will deeply care about them, do

everything they can for them, and have knowledge that can help them.

|

| L'Uomo Vitruviano by Da Vinci |

The desire to like the world is why a person can want to be a doctor. We see the great possibility of medicine, through research and discovery, to cure diseases and lessen human suffering. We see, through our studies, the amazing wonder and beauty of the human body, with its astounding complexity and great unity. We see that there is a means, through the knowledge of medicine, to respect ourselves for making people's lives better, healthier, and stronger.

Contempt

I will give an example of contempt in

medicine: Everyone has heard the criticism that medicine can be cold and

technical, and doctors can be unfeeling. We all have the question of how much

to feel for our patients. I certainly have this question. It is true that

insurance companies force us not to spend enough time with our patients, but

there are other reasons for coldness in medicine.

I will give an instance from my own

experience: As a medical student, I did a rotation on a ward in a city

hospital. The hospital was very overcrowded and one patient's bed had been

placed in the hallway. In that position, it was necessary for me, and many

others, to walk past his bed as we went about our business during the day. He

was an older black man and I noticed that several times he had the covers

pulled over him. Sometimes, if I saw him looking my way, I would nod as I

walked by. I am sorry to say that I once heard an intern speak of this man very

disrespectfully—he called him a "dirt bag.” I'm very ashamed that I didn't object to this despicable way of

talking about a person.

I learned that the man had alcoholic

hepatitis. His name was Mr. Ragland. I felt that it was difficult to relate to

him; an elderly black man who seemed so ill. I was a young white person who didn't drink, was

never seriously ill, or in a bed in a hospital, and I certainly had never

endured poverty as this man clearly had. I felt uncomfortable as I walked past

him.

I spoke of this to teachers of Aesthetic

Realism who, in turn, asked me if I ever felt like I wanted to pull the covers

over myself and not have to deal with things, and get away from a world I saw as cold and

unfriendly. I answered in the affirmative.

It was pointed out to me that getting away from the world, seeing it as

against him, could have been a major motive in this man's drinking.

When I saw Mr. Ragland again on the ward

I began talking to him and gradually found out more about him. He had been a

bricklayer who made very tall industrial chimneys. One day as he did his job he

was struck by lightning and he fell from a great height. Though lucky to have

survived he was left permanently in pain, crippled and unable to work. He spoke

of his wife, who was deceased, and his children, who didn't get to visit him

often.

I saw him in a new way after that. We

became friends and I didn't walk past him coldly any more, and I was very sad

when he later died.

I felt prouder of myself because I felt I

had been more the kind person and doctor that I wanted to be. The lesson I was

learning was that a person comes to the hospital with a lifetime of experiences

and many feelings we are unaware of and we may not take the time to consider,

and that people we can see as so different from ourselves aren't really.

So why hadn't I been interested in him

before? The answer is that I didn't see this person's feelings as important or

even real. I didn't think I could learn anything important from him. There were

many things that seemed important to me but being affected by patients was not

one of them. So while I hadn't used any cruel epithets about him, I still had

seen him as not worth my interest.

We don't want to see a person as having

the same depth and feeling as ourselves. We save our thought for ourselves. We

can see people in terms of their illness, in terms of how quickly we can move

on to the next case, what the work-up will be. Thinking about another person

takes time away from our own comfort. This approach to medicine, taken far,

makes us cold and it is a form of contempt.

Economics and Medicine

We can be confronted with the choice of

making a lot of money in a position that is less useful versus another position: less lucrative, but

more useful, and more suited to what we really want to accomplish. I was

fortunate to be brought up in a family that was conscious of economic injustice

in our society. My parents fought for social justice and didn't want to

compromise on economic issues. Yet as I was becoming a physician I began to

make choices about my career that involved having a lot of money, and thinking

about which field would seem the most glamorous and prestigious, and I thought

less and less about how I would feel most useful and where my talents and

interests really were. The desire I had to help people as a doctor, which

started when I was quite young, became increasingly less important in my

decision making, but I was fortunate to read these passages by Eli Siegel in Self and World, about the two ways of mind that can be had by a physician:

When Dr. Major began to practice there

were two confluents in his mind: one flowed towards fees and position and

conspicuous respectability; the other towards greater and greater knowledge,

research, pervasive and deep usefulness. [p. 284]

And later there are these wonderfully

clear and kind words:

Doctors, like other people, want to like

themselves for the right reasons. A right reason is the feeling that one is

useful. The feeling of usefulness is basically this: by the existence of

oneself other things are larger, more beautiful, happier; take on new value.

The deep belief that one is useful is equivalent to pride. After all, when we

like ourselves there are various inevitable criteria. We cannot like ourselves

if the relation we have to other realities is not acceptable. A doctor, then,

is impelled by the motives of all: the motive to be comfortable, the motive to

be pleased with oneself accurately. [p. 286]

Though it may not seem so, the desire to

put one’s making a lot of money and wanting to be

prestigious ahead of what things may be asking of you, and where you can do the

most good, is a form of contempt. The world gives us a chance as doctors to be

really proud of ourselves, and yet we can let something else take over.

It is contempt for physicians to see

patients in terms of how much money can be made from them. It is contempt, too,

for insurance companies to see the medical needs of people in terms of profit.

It is also contempt that Americans and their political representatives have

allowed millions of other Americans to go without adequate, or even any,

insurance, making for needless illness, suffering, and death. Eli Siegel asked

this very important question: "What does a person deserve by being a

person?" The answer, in relation to medicine, can only be that every person deserves the right to as healthy and

happy an existence as possible.

How can we like the world when there is

so much that is unlikeable in it? Aesthetic Realism says the one way to like

the world honestly is through seeing it as the "aesthetic oneness of

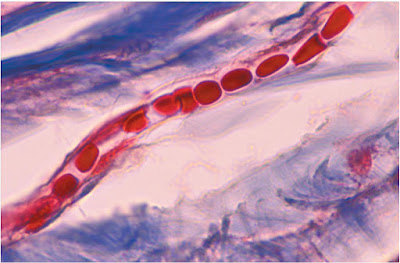

opposites.” For example, the red blood cell’s ability to adapt and change while maintaining itself is a oneness of

opposites. The outer membrane of the red blood cell is amazingly flexible so

that it can get through the tiniest of spaces and still keep itself intact in

order to deliver its precious cargo of oxygen.

|

| Red blood cells squeezing through capillary - Centre for Blood Research, University of British Columbia |

Nature used biochemistry to create the oneness of remarkable flexibility and great toughness because that's

what it needed to do the job. Not only is this oneness of the opposites of

flexibility and strength why the membrane works so well, it is an element in

the beauty of its design. It has us like the world when we see it in action.

The ability of the red blood cell to get

through difficult situations while maintaining its integrity is something we as

people would like to have. For as we meet different and difficult situations we

have to keep our unity of purpose intact. There is something to be learned from

the red blood cell here.

In the physiology of the iris of the eye

we see that sympathetic nerve stimulation causes tiny muscles to dilate the

pupil to allow in sufficient light, while simultaneously parasympathetic

excitation constricts the pupil to keep excess light out. Nature in its design

uses these two simultaneous yet opposing forces to make for exactly the right

pupil size for the particular brightness of an object. The opposite forces can

be seen as only antagonistic, yet we can also see that they need each other and

are working together for the same purpose. When forces are in antagonism yet we

realize that the antagonism arises from, has a useful, even kind purpose, we

see beauty. And this is a way of liking the world.

Through careful looking I have seen many

instances like that in the iris: in the heart, the pancreas, the stomach, the

lungs, and much more, where opposites have been made one. In fact I believe,

and Aesthetic Realism would maintain, that every instance of human physiology

when looked at carefully will be seen to be a situation where opposites have

been made one by nature, and as such are examples of its beauty, and point to

why the structure of reality is aesthetic and can be liked.

In fact, the opposites as one are the

structure of all Nature, from the physics of the atom where Energy and Matter

are one,

to the physiology of the iris with its friendly and yet competing

muscles and nerves. Every scientist and indeed every person should have this

essential knowledge.

|

| hydrogen atom - A.S. Stodolna |

Aesthetic Realism is not only of great

usefulness to the medical field. It is needed by all the professions and all

people as individuals. It has not been seen yet by any philosophy or way of

seeing the human mind, that the purpose of our lives "is to like the world

and ourselves at the same time." As such it is so important that it be

studied by everyone. That battle in the self between contempt and respect, as I

described in other doctors and in myself, is in all the professions and all

people. The world can only truly be kind when this is a subject of general

study.